Groundwater 101

GROUNDWATER: MAKING THE INVISIBLE VISIBLE

With a large population and only 14 inches average annual rainfall, the LA Basin remains a water conundrum. The 10 million people that live in LA County depend on clean, safe and reliable drinking water to use at home at work and in the commercial industries that sprawl throughout the county. However, nature cannot meet the region’s demand through local stormwater alone.

Groundwater has always played an integral role in the water supply for the region and is poised to play a primary role in our drought resiliency. Understanding the region’s groundwater journey reveals how this critical resource will secure the LA Basin’s water security for decades to come.

OUR UNSEEN RESOURCE

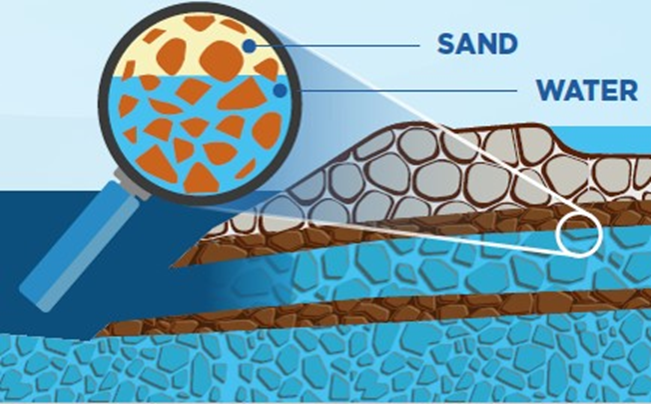

Early in the LA Basin’s history, groundwater played a central role in providing water to the residents, farms, and industries of the region. Groundwater is the water that exists in the naturally occurring aquifers that are layered beneath our feet. Aquifers refer to sediment layers that are composed of porous gravels or sands and can thus hold and transport water. Aquifer layers are separated by layers of less porous silts or clays referred to as aquitards.

Luckily, the LA area has plenty of naturally occurring aquifers that were produced over millions of years, long before humans came through and settled in the area.

.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&w=2000&h=2000&fit=max&or=0&s=e0f4a60d8f3aebef083094ca443739fc)

MANAGING AND PROTECTING OUR PRECIOUS GROUNDWATER

In the LA area, groundwater is a highly regulated and managed resource. For example, the Water Replenishment District (WRD) is a special government district that was formed by a vote of the people in 1959 to manage and protect two of the most utilized groundwater basins in the nation – the Central and West Coast Basins. These two basins are located in southern LA County and provide nearly half of the water supply for the 4 million people that live in the 43-city service area.

In the 1960s, the groundwater in the region was adjudicated—meaning that the courts set limits on who could pump and how much they could pump annually. These limits, along with managed aquifer recharge from WRD has meant that the groundwater basins recovered from severe overdraft in the early 1900s and are now sustainably managed with local water replenishment supplies which include stormwater capture and recycled water.

REPLENISHING THE BASINS

WRD ensures enough water finds its way back into the ground to keep our basins healthy. To get the job done, WRD works with the LA County Department of Public Works who own and operate two important water infrastructure systems: the spreading grounds and the seawater barrier injection wells.

The LA County San Gabriel and Rio Hondo Spreading Grounds are large pond-like basins carved out by the Army Corps of Engineers in the 1930’s. Initially created for flood control, these basins access a special geologic area where multiple aquifers meet at the earth’s surface. The result is an area that can act like a large sponge which allows large volumes of water to soak into multiple aquifers below the surface. These basins can infiltrate water at a rate of about 1 foot per day and are the primary source for replenishing the Central Basin.

.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&w=2000&h=2000&fit=max&or=0&s=664881ba4c49ce29686b154d33d25f78)

.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&w=2000&h=2000&fit=max&or=0&s=e108adaaea87a2c20c0e687cd4c343ee)

Along the coast, replenishment takes a different form. Freshwater injection wells owned and operated by LA County Department of Public Works are used to actively pump freshwater into the underlying aquifers. The injection wells serve two purposes, they create a pressure gradient that prevents seawater from intruding into the groundwater aquifers and they help replenish the West Coast Basin at the same time.

.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&w=2000&h=2000&fit=max&or=0&s=18bde8ba8addb722da8a5687e9a5f020)

.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&w=2000&h=2000&fit=max&or=0&s=84d1fc2512f1211cd6a34f7c59ef9b8d)

Through surface spreading and freshwater injection, WRD is able to keep the Central and West Coast Basins filled for groundwater pumpers such as utilities and municipalities to use for their residential customers. WRD is also responsible for monitoring groundwater quality through a robust monitoring network.

.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&w=2000&h=2000&fit=max&or=0&s=6560204b970c6d2a4cd892e250b9bfed)

THE SUSTAINABLE GROUNDWATER CYCLE

When WRD was first formed, the district supplemented local stormwater with imported water from the Colorado River or Northern California. The imported water sources rely heavily on snowmelt from the Colorado Rockies or the Sierra Mountains, respectively, that is transported to the LA area through a series of aqueducts and pump stations.

Recognizing early on that recycled water could be a beneficial local source for replenishment, WRD started using treated wastewater for groundwater replenishment as early as 1962. Over the decades WRD steadily increased its use and production of recycled water sources until it created the capacity to replenish the groundwater basins with stormwater and recycled water solely – no more need for imported water. This was achieved through the district’s Water Independence Now Program (WIN).

The completion of WIN meant that WRD could replenish the groundwater which meets nearly half of the water demand for southern LA County with a locally sustainable supply. This will create drought and climate resiliency and has already paid off during this current drought because WRD no longer relies on imported water supplies that are in very high demand.

.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&w=2000&h=2000&fit=max&or=0&s=2319d0a3499da121e895fdc85a723e48)

.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&w=2000&h=2000&fit=max&or=0&s=1b5f713d2b333581d0c08e35cbd38dbc)

THE ALBERT ROBLES CENTER FOR WATER RECYCLING AND ENVIRONMENTAL LEARNING

The keystone project of the WIN program is the Albert Robles Center (ARC), an advanced water treatment facility that purifies 14.8 million gallons of water per day. The water is treated with a multi-barrier process that includes ultrafiltration, reverse osmosis, and ultraviolet light with advanced oxidation.

Water from ARC is then delivered to the San Gabriel Spreading Grounds for surface spreading. This offset the last need for imported water to replenish the basins and completed the WIN program.

.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&w=2000&h=2000&fit=max&or=0&s=390feaedb21ac5f9dd0e114c81173c5a)

MAXIMIZING REGIONAL GROUNDWATER RELIANCE

With the WIN program complete, WRD has successfully secured a locally sustainable water supply for groundwater replenishment. However, that accounts for just under half of the regions water use. If we can maximize the use of groundwater and then leverage the ample groundwater storage space that is available in the basins, we can create a region that is dependent upon a local groundwater supply that is replenished using locally sustainable supplies. WRD calls this WIN 4 ALL—a 2040 regional water independence initiative.

.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&w=2000&h=2000&fit=max&or=0&s=3a2277eef2f44aebba580a9b31ac45dc)

The keystone project for the WIN 4 ALL program is the Regional Brackish Water Reclamation Program (RBWRP). This is a project that will cleanup an historical brackish water plume that was created in the early 1900s due to over-pumping in the region. As seawater flowed into the freshwater aquifers, the groundwater was contaminated with salty water, or brackish water, that cannot be used as drinking water.

By remediating this 600,000-acre-foot (20 billion gallons) brackish water plume, a new source of drinking water will be created, along with ample groundwater storage space. That space can be filled with recycled water and used as a bank for dry water years.

.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&w=2000&h=2000&fit=max&or=0&s=8d4ba943ae93b67385c36d02cdbc1075)

COMMITTING TO CLEAN WATER FOR ALL

Another important piece of the equation is ensuring that all groundwater users are pumping their full water rights allocations. We can’t achieve regional groundwater reliance if some of the area’s groundwater wells are not being used due to contamination or need for upgrades.

WRD is committed to making sure that every community has access to high-quality, affordable, and sustainable drinking water. The WRD Safe Drinking Water Program has operated since 1991 and is intended to promote the cleanup of groundwater resources at specific well locations through the installation of wellhead treatment facilities that remove contaminants (naturally occurring or human-made) and delivers the treated water as drinking water. Projects implemented through this program are accomplished in collaboration with well owners.

.png?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&w=2000&h=2000&fit=max&or=0&s=641b66fa181d7e91b5cd038abfc0d745)

The Safe Drinking Water Program now includes a third component, the Disadvantage Communities (DAC) Outreach Assistance Program, which aids water systems in underserved areas with applying for State funding. The first project completed under the DAC program is the Maywood Mutual Water Company No. 2 wellhead treatment project that addressed the naturally occurring contaminants of manganese and iron through the help of Speaker Anthony Rendon, the State Water Resources Control Board and WRD.

With the right support and funding these simple, yet oftentimes overlooked projects will increase the use of inexpensive groundwater in communities that would be disproportionately burdened by the alternative of buying imported water.

THE GROUNDWATER JOURNEY CONTINUES

While a large portion of our groundwater resources are being replenished with sustainable supplies, there is still much of the region that depends on imported water supplies. To meet the challenges of climate change and future droughts, the water industry is laser focused on increasing recycled water supplies, maximizing groundwater usage, and optimizing groundwater storage.

This newest effort can be viewed on the scale of another Mullholand moment, where regional stakeholders must work together on ambitious infrastructure projects that will serve the LA Basin for generations. The good news is that the partnerships are underway, the groundwork is set, and a drought-resilient water future is within reach.